How the ECJ’s Decision on Malta Could Impact Europe’s CBI Programs

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Definition

- Malta's Investor Program: An Overview

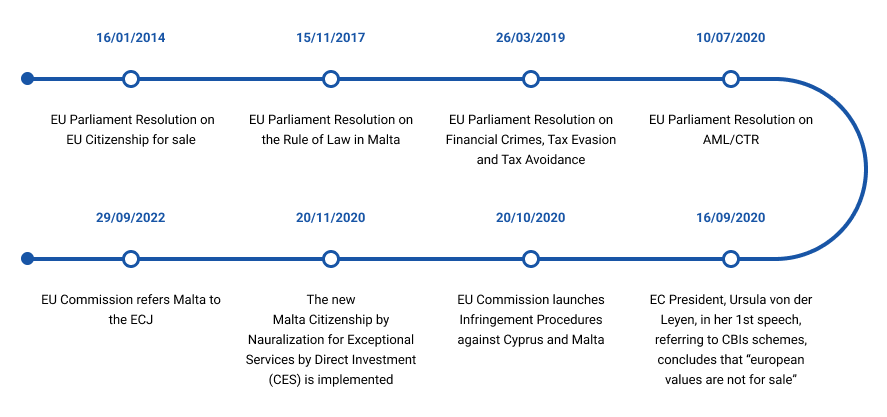

- The European Commission’s actions against CBI schemes: A timeline

- Allegations against CBIs programs by the EC and the EP

- Malta’s response to the accusations

- Exploring the ECJ judgment's broader implications on CBI schemes around Europe

- Looking toward a critical juncture for national sovereignty and EU law

- References

Foreword

As the global landscape of citizenship by investment (CBI) and residence by investment (RBI) schemes continues to evolve, the European Court of Justice’s (ECJ) impending decision on Malta’s CBI program marks a critical juncture with far-reaching implications. At Global Citizen Solutions, we recognize the significance of this moment not only for Malta but for the entire European Union and the global mobility industry at large as it could set a precedent impacting similar CBI programs across Europe.

This report, focusing on the future of CBI schemes in Europe following the ECJ’s decision, is emblematic of our commitment to deepening the discourse on these critical issues. By dissecting the intricate interplay between national sovereignty, economic strategies, and EU legal frameworks, we aim to shed light on the complexities and challenges the industry faces. It is with this understanding that we are proud to announce the launch of our Intelligence Unit department, a dedicated effort to provide a deep analysis of and fresh insights into the dynamic sectors of global mobility, wealth management, and RCBI schemes. In launching this department, Global Citizen Solutions reaffirms its dedication to enhancing understanding and fostering dialogue on the pivotal topics of global mobility and investment migration.

Our Intelligence Unit is poised to contribute significantly to the global conversation on global mobility, offering a reliable source of information for industry operators, clients, and stakeholders. We aspire to increase our participation in the global conversation and to influence it positively, providing actionable insights and evidence-based analysis. Through our work, we aim to support informed decision-making and strategic planning for all involved in the RCBI space.

As we navigate these transformative times, we intend for the insights presented in this report and the ongoing work of our Intelligence Unit will serve as valuable resources for understanding the complexities of global mobility, wealth management, and citizenship by investment schemes.

Intelligence Unit Team

Introduction

The European Commission’s initiation of an infringement procedure against Malta concerning its citizenship by investment (CBI) scheme has brought significant attention to the intersection of national sovereignty, economic policies, and European Union (EU) law. At the heart of the matter are concerns regarding the compliance of Malta’s CBI programs with EU standards and principles as well as the Member States’ legislative competence to regulate issues related to residence and nationality acquisition. The implications of this procedure extend beyond Malta’s borders, impacting the European Union as a whole and shedding light on the complexities of citizenship and residency by investment programs in today’s interconnected world. In this overview, we delve into the significance of the European Commission’s actions, examining their implications for Malta, the EU, and the broader context of citizenship by investment programs.

Definition

CBI: Citizenship by investment programs1 can be defined as formal, bureaucratic schemes that enable individuals to naturalize on the basis of a defined donation to a government or investment in a country. They establish minimum investment amounts and types, have a clearly defined and bureaucratic application procedure, and can be applied for by anyone who fulfils the requirements. Formalization is an essential element of this definition as it distinguishes CBI from merely the grant of citizenship based on individualized negotiations with a government or set of officials2. They differ from residence by investment schemes (RBIs) as the latter grants the right of residency in the country of relocation without granting citizenship and the rights attached to it. CBI programs attract investments to real estate, infrastructure and development sectors, boosting countries’ economies. This could be particularly appealing for smaller or economically weaker Member States looking for ways to stimulate economic growth and attract foreign capital.

Malta's Investor Program: An Overview

Introduced in 2013, Malta’s Individual Investor Program (IIP)3 has been a cornerstone of the country’s efforts to attract foreign direct investment and spur economic growth.4 The program was created to offer eligible individuals and their families the opportunity to acquire Maltese citizenship in exchange for a substantial financial commitment, investment in government-approved assets, and meeting specific eligibility criteria.

The initial version of the IIP required applicants to make a non-refundable contribution to the Maltese National Development and Social Fund, invest in government-approved bonds or securities, and undergo stringent due diligence procedures. Successful applicants were granted Maltese citizenship, granting them rights and privileges associated with European Union citizenship, including visa-free travel within the Schengen Area.

In October 2020, the European Commission filed infringement proceedings against Malta and Cyprus5 regarding their Citizenship by Investment (CBI) schemes. The Commission contended that the provision of nationality – and consequently EU citizenship – by these Member States, in return for a predetermined payment or investment and without a “genuine connection”” or “genuine link” to the Member States involved, contradicted the principle of sincere cooperation outlined in Article 4(3) of the Treaty on European Union. Additionally, the Commission stated that such practice undermined the integrity of the EU citizenship status outlined in Article 20 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European 6Union.

Following the Commission’s filing, Malta adopted new regulations on the Citizenship by Naturalization for Exceptional Services by Direct Investment Scheme (CESDI)7-8, adapting the previous program. These changes have been aimed at addressing concerns raised by international stakeholders, enhancing program integrity, and ensuring compliance with EU law and standards. Revisions to the Malta CESDI have included adjustments to eligibility criteria, investment requirements, due diligence procedures, and transparency measures. Amendments were made to align Malta’s citizenship by investment programs with evolving international standards and best practices in the field of citizenship and residency by investment.

To qualify for the new Maltese Citizenship program, applicants must:

-

- Prove residency in Malta for 36 months, which can be reduced to 12 months with an exceptional direct investment of €600,000 to €750,000.

- Either purchase residential property in Malta valued at a minimum of €700,000 or lease property with an annual rent of at least €16,000, suitable for the applicant and dependents, for a minimum of five years from the citizenship certificate issuance date.

- Make an exceptional direct investment in Malta as per the Citizenship for Exceptional Services Regulations.

- Donate at least €10,000 to a registered NGO or society in fields such as philanthropy, culture, sports, science, animal welfare, or the arts, approved by the Agency, before receiving the naturalisation certificate.

Timeline of processing the Malta CESDI:

From the time the application is submitted for a Maltese residence permit to the time the citizenship is granted, the scheme’s application process takes around 12-36 months, depending on the investment.

-

- Citizenship application: After 12 months or 36 months from Residence, the agent presents the Citizenship application to the Agency.

- Update due diligence: The Agency refreshes its previously conducted due diligence on the residence application of the Applicant and submits its conclusive findings to the Minister.

- Investment: The Applicant meets the requirements for Exceptional Investment, Donation, and Property.

- Oath of Allegiance: Applicant is granted Maltese Citizenship and is issued with a Certificate of Naturalisation.

- Monitoring: Agency conducts continuous monitoring for five years.

The European Commission’s actions against CBI schemes: A timeline

In the past eight years, both the Commission and the Parliament have consistently addressed concerns related to investment migration. The Parliament has taken a stance through the adoption of several non-binding resolutions9, urging EU Member States to discontinue such programs. In contrast, the Commission took more decisive action by commencing infringement procedures against Cyprus and Malta in 2020. This effort culminated in the Commission bringing Malta before the Court of Justice on September 29, 202210.

Timeline

‣ 15/01/2014 – Plenary debate in the Parliament about the Malta’s Individual Investor Program (IIP) scheme11, when the EU Justice Commissioner, Viviane Reading states that: “One cannot put a price tag” on European citizenship.

‣ 16/01/2014 – Following Readings’ speech, the Parliament adopts the “Resolution on EU Citizenship for sale,” calling Malta to “bring its current citizenship scheme into line with the EU’s values12.”

‣ 29/01/2014 – The Commission publishes a memo with a Joint Press Statement from the EC and the Maltese authorities on IIP13. The Maltese representatives present their intentions regarding further amendments to the regulations issued under the Maltese Citizenship Act (L.N.450 of 2013), mainly by including legal residence requirements.

‣ 15/11/2017 – The Parliament adopts a resolution on the rule of law in Malta14 reiterating concerns regarding Citizenship by Investment Schemes in Malta and other EU Member States. It also urges Malta to disclose “purchasers of Maltese passports” and their associated rights, along with safeguards ensuring residency requirements.

‣ 26/03/2019 – The Parliament adopts a Resolution on Financial Crimes, Tax Evasion and Tax Avoidance15, concluding that the “potential economic benefits of CBI and RBI schemes do not offset the serious security, money laundering and tax evasion risks they present” and calling “on Member States to phase out all existing CBI or RBI schemes as soon as possible.”

‣ 10/07/2020 – The Parliament adopts a Resolution16 on a comprehensive Union policy on preventing money laundering and terrorist financing calling on the Member States to “phase out all existing [CBI] or [RBI] schemes as soon as possible.”

‣ 16/09/2020 – In her first speech, the President of the EC, Ursula von der Leyen vowed to defend “the rule of law and the integrity of our European institutions” and she explains that one of the targets would be the sale of golden passports: “European values are not for sale,”she 17concluded.

‣ 20/10/2020 – The Commission launches infringement procedures against Cyprus and Malta regarding their investor citizenship schemes also referred to as “golden passport” schemes18.

‣ 20/11/2020 – Malta adopts subsidiary legislation on Citizenship by Naturalisation for Exceptional Services by Direct Investment Scheme19 aiming at enhancing transparency on disqualification grounds based on criminal convictions regarding money laundering.

‣ 28/03/2022 – The Commission recommends that any Member State that had granted citizenship to Russian or Belarusian nationals through an investor citizenship scheme should promptly undertake an assessment to determine whether the naturalization of these individuals ought to be revoked on the grounds of significantly supporting, in any capacity, the war in Ukraine or other actions by the Russian government20.

‣ 29/09/2022 – The Commission refers Malta to the European Court of Justice21, restating that granting EU citizenship in return for pre-determined payments or investments without any “genuine link” to the Member State concerned is not compatible with the principle of “sincere cooperation” enshrined in Article 4(3) of the Treaty on European Union, and with the concept of Union citizenship, as provided for in Article 20 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

‣ 29/09/2022 – The Maltese Ministry for Home Affairs, Security, Reforms and Equality releases a statement22 strongly rejecting the interpretation of the EC on the principles provided in Article 4(3) of the Treaty on European Union, and with the concept of Union citizenship, as provided for in Article 20 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Maltese authorities restated the CESDI operates “on the basis of robust due diligence processes which address the risks related to money laundering and the financing of terrorism.”

Allegations against CBIs programs by the EC and the EP

“Less stringent requirements” and “a genuine link”

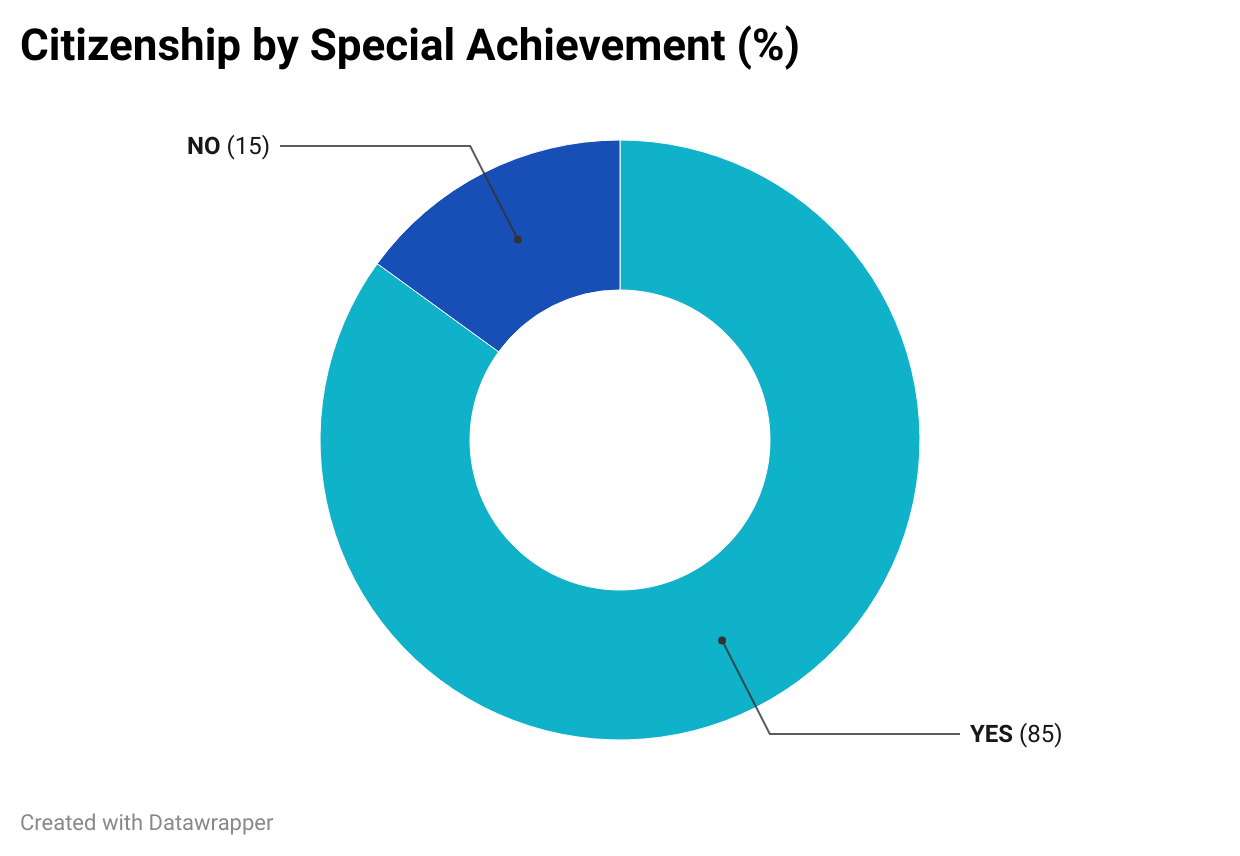

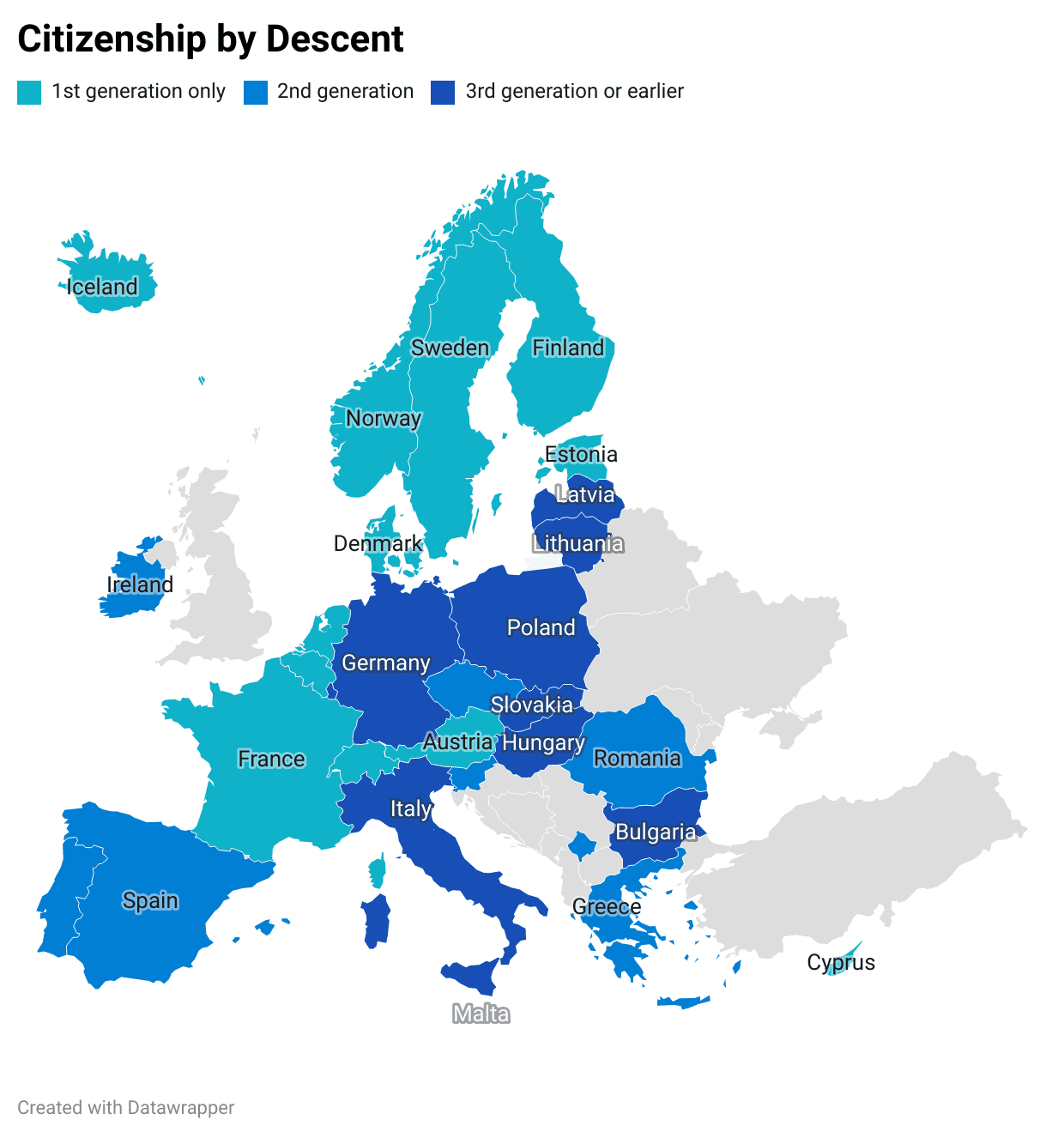

The Commission asserted that the acquisition of citizenship through CBIs entails less stringent requirements compared to other forms of naturalization23, which typically requires several years of permanent residency in the destination country as well as proof of language proficiency and socio-cultural exams. However, certain Member States grant nationality by descent based on blood criteria (see chart below) to individuals lacking any other connection or affiliation with the destination country. According to Dmitry Kochenov, such interpretation expresses a nationalist approach by “fetishizing blood as the paragon for building a just human society24.”

Italian legislation, for instance, permits the acquisition of citizenship by descent without limitations on the degree of ancestral lineage25. To claim Italian citizenship and turn it into a passport, it is sufficient to prove that the Italian male ancestor – also female, if born after 1948 – with no generational limit, never renounced Italian nationality voluntarily. The procedure does not include any residence or language requirements26. Additionally, Italian law historically permitted naturalization through marriage for individuals lacking any relationship whatsoever with the country, such as proof of physical presence or residence, and until a few years ago, did not mandate language proficiency tests for such naturalized individuals27. It demonstrates that in cases where ‘blood’ is a determining factor, other considerations — such as residence, place of birth, and income — typically hold little to no significance28.

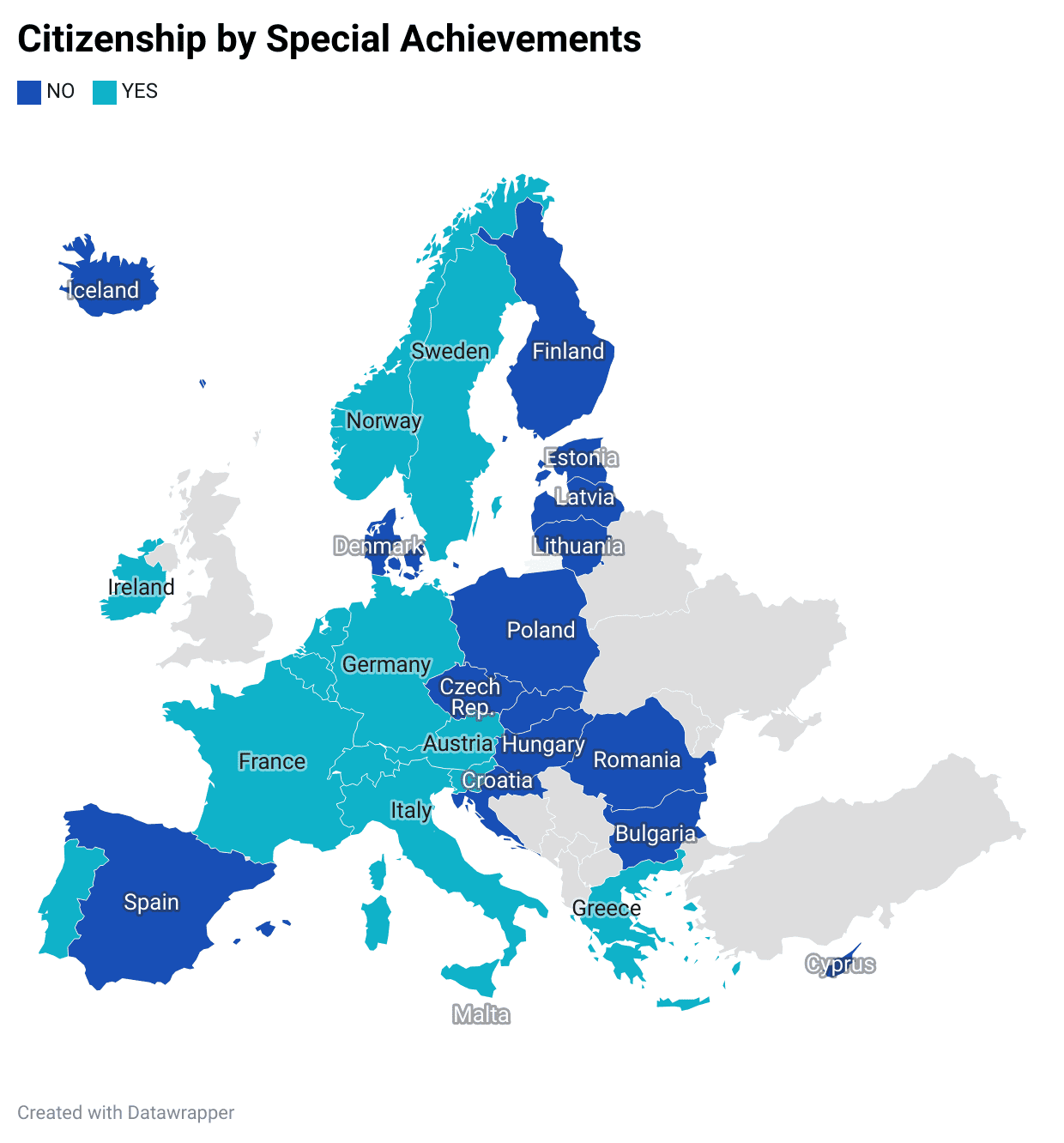

Another interesting case is Austria’s pathway to citizenship, not through investment, but by recognizing individuals who have made extraordinary contributions in fields such as science, arts, culture, sports, or economics29. This “residence for special achievements” route is distinct in that it does not require a financial investment or a prolonged period of residence as prerequisites. Instead, it evaluates the individual’s potential to offer significant non-economic benefits to the Austrian state through their exceptional talents or accomplishments.

The European Union’s critique of CBI programs often revolves around the absence of a ‘genuine link’ between the applicant and the member state, raising concerns about security, transparency, and the integrity of EU citizenship. These programs are scrutinized for potentially allowing individuals to acquire EU rights and mobility without a substantive connection to the country of citizenship. In contrast, Austria’s program, while also not requiring a traditional genuine link like residency or cultural integration, is perceived as less of a risk. However, this leads to a debate about consistency in the EU’s approach. If the lack of a genuine link is a significant concern for the EU, the question arises as to why Austria’s citizenship route, which also does not necessitate a conventional genuine link, does not face similar criticism. This situation highlights a potential inconsistency and discrimination in the EU’s stance on citizenship policies, suggesting a need for a more uniform standard in evaluating different national schemes within the context of EU principles, collective interests, and state sovereignty.

Jus Sanguinis: Attaining European Citizenship through Lineage

The acquisition of rights and privileges by jus sanguinis (right of blood) originates from a feudal tradition based on familial lineage. By extrapolating this principle to the transmission of citizenship in the context of a state entity, it propagates the notion of a purportedly pure lineage of individuals entitled to the rights and privileges associated with certain nationalities. As Kochenov rightly puts it, “EU citizenship is sacred and rooted in the native possession of pure European blood providing a ‘genuine link’ to Europe30.” In any case, international law and the broader theory of statecraft position citizenship acquisition and loss within the purview of state sovereignty, thereby permitting states to designate blood ties as “genuine links.” The same set of laws also permits states to grant nationality to individuals for special or extraordinary achievements and for those who donate a certain amount of money or invest in the country according to the regulations established in their laws.

Indeed, many countries offer naturalization programs for special or extraordinary achievements (see chart below). These schemes typically rely on subjective criteria related to the personal characteristics of the applicants, which may be associated with intellectual, artistic, or sporting achievements, or even economic criteria. What distinguishes this mode of citizenship acquisition from CBI programs is that the former is discretionary, whereas the latter are based on general bureaucratic procedures that present formal and transparent requirements for citizenship access. What also distinguishes CBI schemes from citizenship procedures for special or extraordinary achievements is that the latter have never been targeted by the Commission and Parliament, despite also presenting issues related to genuine links and even more problems regarding less stringent processes.

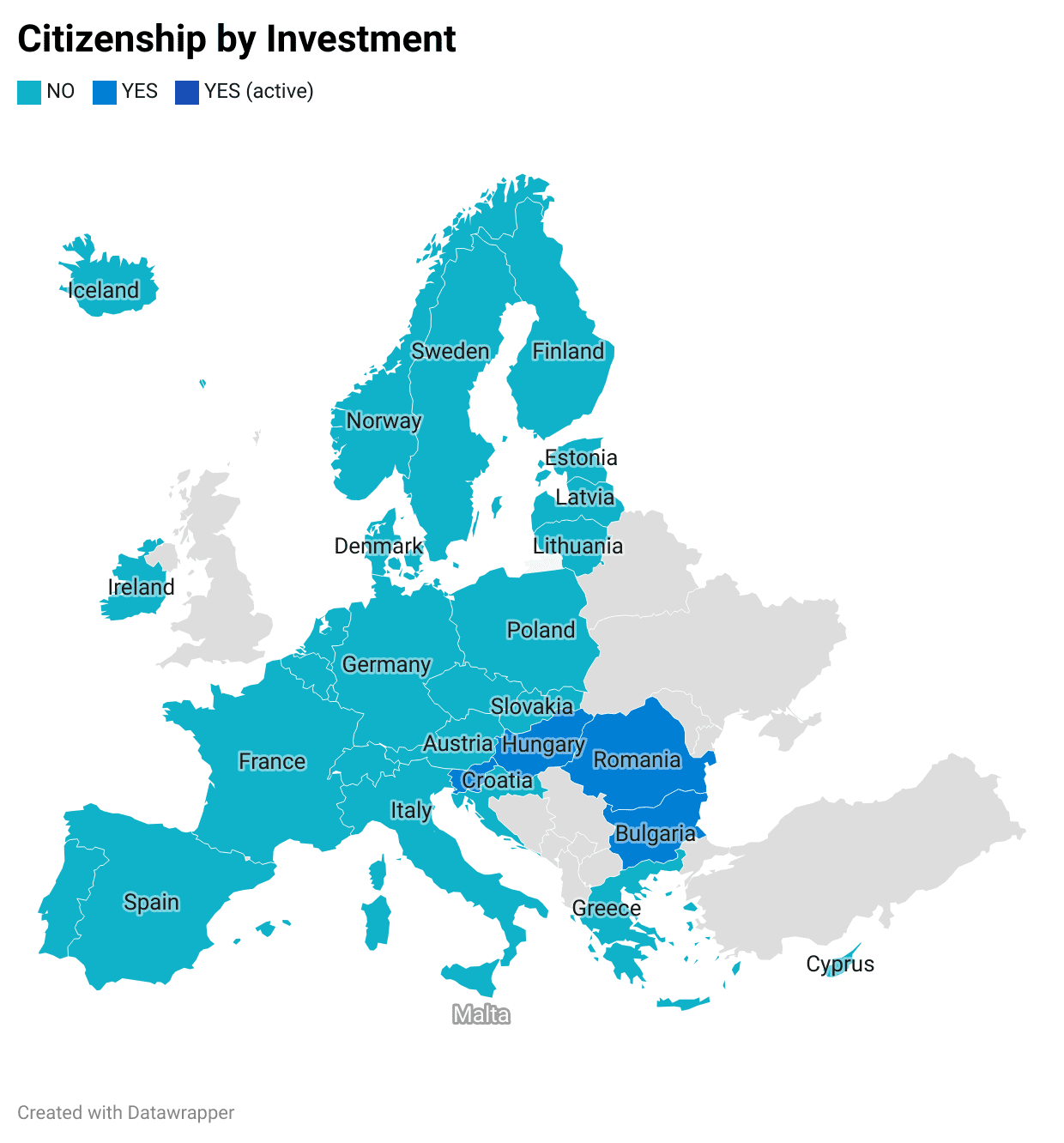

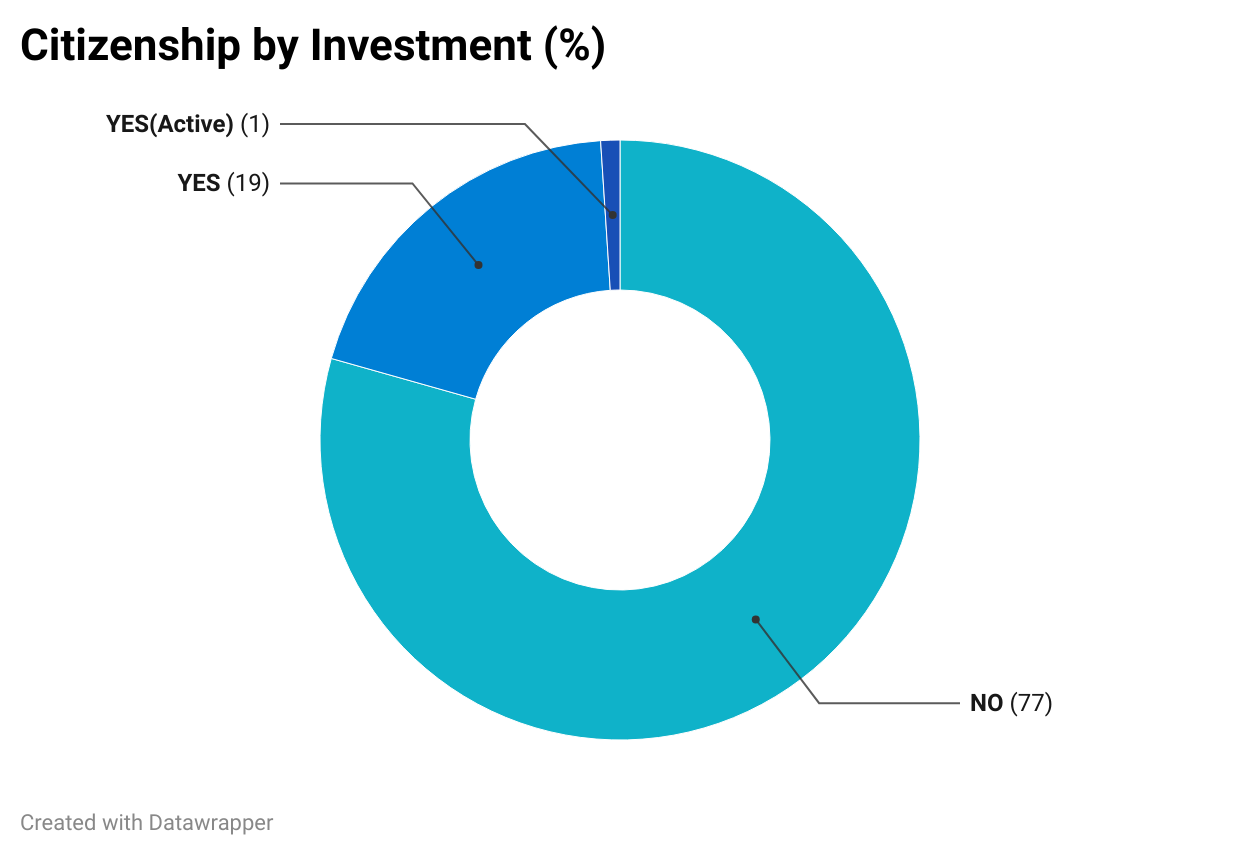

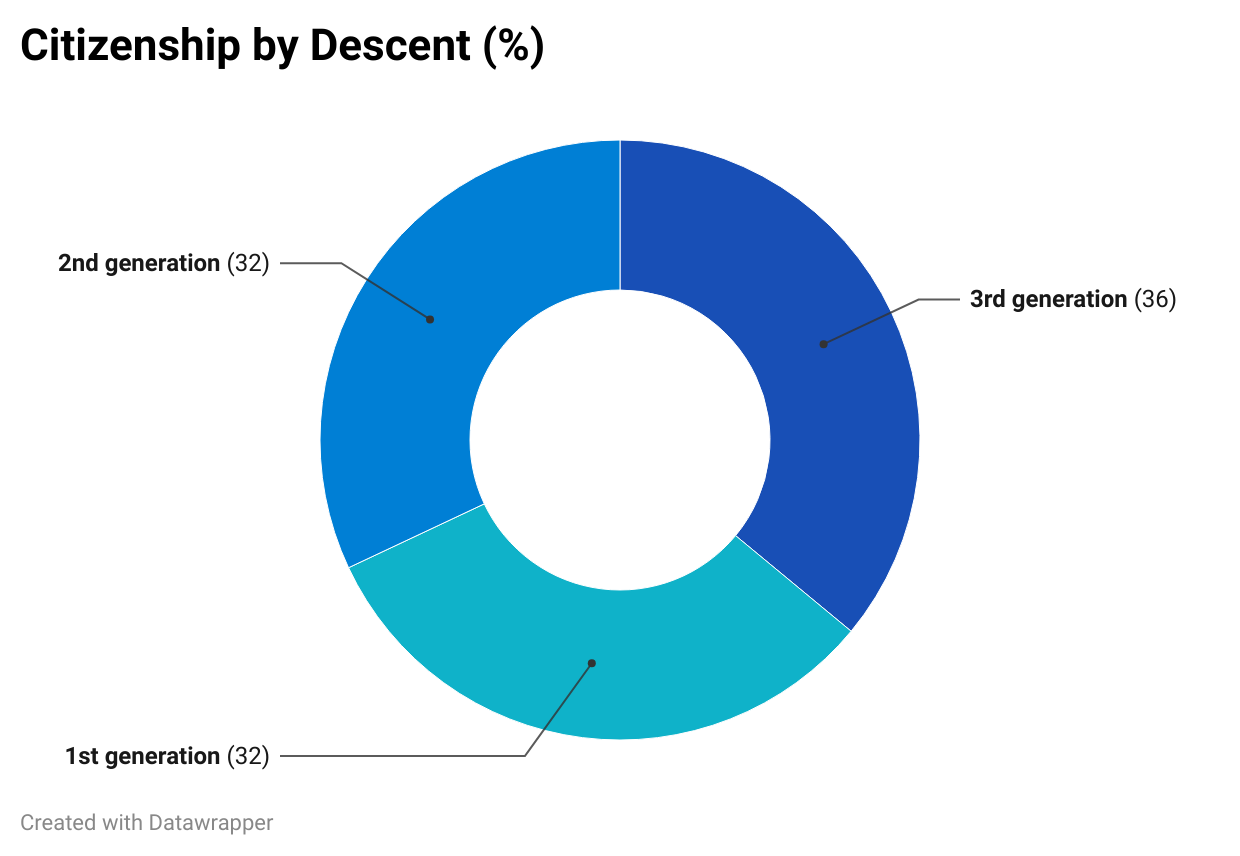

As can be observed in the charts below, most European countries accept citizenship by descent and adopt procedures for special or extraordinary achievements to grant nationality. On the other hand, only four countries have legal provisions for CBI. Nevertheless, these programs have been subject to constant criticism from the Commission and Parliament, unlike other programs that may present more issues related to the “genuine link” and a less stringent procedure.

According to the data provided in the charts below31, currently, only Malta operates an active Citizenship by Investment (CBI) program within the European Union. Countries such as Romania, Bulgaria, Slovakia, and Cyprus have legal provisions for such schemes but are not accepting applications. On the other hand, 85 percent of EU countries provide for the granting of citizenship through special or extraordinary achievements, in discretionary processes where a genuine connection can also raise some questions. Furthermore, all European Union countries have legal provisions for citizenship by descent32, and in countries such as Italy, Hungary, Poland, and the Baltic states, there is no limit on the degree of ancestry for the granting of citizenship, allowing individuals with no direct link to the country to access citizenship. However, only the CBI programs are being targeted by the Commission and the European Parliament.

In this context, if the concern of these bodies relates to issues of economic illegality such as money laundering, tax evasion and corruption, it would be more appropriate to urge that countries implement strict and transparent access and vetting criteria. According to the Investment Migration Council (IMC), the obligation to phase out such schemes not only represents an abuse of power by EU bodies but also fails to address the problem of economic crime within the bloc. Moreover, this requirement deprives countries of the opportunity to receive investments that contribute to national development.

Member States’ legal competence to regulate citizenship

Citizenship delineates a legal connection between an individual and a state. The authority to govern citizenship, according to Convention on Certains Questions Related to the Conflict of Nationality Law 33 34 stands as a pivotal and singular facet of state sovereignty, with international law imposing limited constraints on states’ rights to regulate citizenship. These constraints primarily encompass prohibitions against statelessness and the arbitrary revocation of citizenship. 35.

EU citizenship is contingent solely upon national citizenship, as individuals qualify as EU citizens only when they possess the citizenship of an EU Member State36. EU legislation is founded upon the principle of conferral37, which stipulates that any competences not explicitly granted to the Union are retained by the Member States. Consequently, laws pertaining to nationality fall squarely within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Member States, as these powers were never transferred to the EU.

According to these regulations, Member States may continue to define who they wish to consider citizens or not. In this vein, the ECJ has extensively articulated the acknowledgment of Member States’ wide latitude in defining the terms and procedures regarding the acquisition and relinquishment of nationality38. These criteria may relate, as mentioned above, to descent, to birth (territorial ties), to personal characteristics related to extraordinary achievements, or to economic connections that a person may establish with a state when participating in a CBIs scheme.

Thus, the prevailing conclusion suggests that within European and international law, states retain the legal authority to dictate citizenship access. Likewise, academic consensus aligns with this notion39. In addition, in cases such as Micheletti, Zhu & Chen and Tjebbes, the ECJ definitively establishes that it is the laws of the Member States, rather than those of the EU, that prescribe nationality access.

Consequently, it can be deduced that the ECJ ought to render a decision favorable to Malta. This conclusion is underpinned by the assertions of the Court’s case law, the principles of international and European law, and the prevailing academic consensus, all of which concur that the jurisdiction over the norms governing the conferral of nationality resides within the purview of the Member States.

The principle of “sincere cooperation”

The Commission stated that “the grant of EU citizenship based on payment or investment and without a genuine link is incompatible with the principle of sincere cooperation enshrined in Article 4(3) TEU and undermines the integrity of the status of EU citizenship provided in Article 20 TFEU.” Again, the Commission alleged that sincere cooperation demands a genuine link between the individual and the state and reinstates that no genuine link can be established in CBIs schemes.

Free movement is also a concern of the EU when it comes to granting citizenship by investment. Schengen Area is a zone where 26 European countries have abolished their internal borders, allowing for unrestricted movement of people. However, not all EU countries are part of the Schengen Agreement, and not all Schengen countries are in the EU. For example, Norway and Switzerland are part of Schengen but not the EU, while EU members like Bulgaria and Romania are not yet part of Schengen. Therefore, the ability to move freely across Europe is primarily facilitated by the Schengen rules rather than merely by EU membership.

The fact that “the agreement does not have a perfect overlap with the EU countries” refers to the discrepancies between Schengen and EU membership. This impacts how EU citizenship is perceived because while EU citizenship typically confers the right to move and reside freely within the territory of all EU member states, the nuances of the Schengen Agreement introduce additional layers to these rights, affecting mobility to countries that are not EU Member States.

Therefore, “EU nationality has a significant impact on Schengen as well” implies that the granting of EU nationality, especially through schemes like Malta’s CBI, carries implications for the Schengen Area, even if the countries are not perfectly aligned. This raises “another facet of sovereignty issues” because it underscores the tension between national autonomy in deciding who becomes a citizen (and thus, implicitly, who gains Schengen access) versus the collective interest in maintaining control over who can move freely within the Schengen Area. This tension speaks to broader questions of sovereignty, as it touches on the extent to which individual member states can make decisions that have implications beyond their borders within the shared space of the Schengen Area.

The EU’s criticism of CBI programs often hinges on the principle of sincere cooperation, arguing that these programs may conflict with the collective interests of the Union, especially concerning the management of movement within the Schengen Area. However, it’s worth noting that this principle’s application to CBI programs can be seen as somewhat selective, given that other forms of nationality acquisition, such as citizenship by descent (jus sanguinis) or through special achievements, are not typically subjected to the same scrutiny, despite creating similar discrepancies within the Schengen Area and the EU. This could be construed as discriminatory against CBI as a form of nationality acquisition.

The EU has historically accepted that nationality laws are within the domain of individual Member States, and it has not questioned other forms of nationality acquisition that also have implications for EU citizenship and, by extension, Schengen Area rights. The debate over CBI programs thus opens a broader conversation about whether and how the EU can or should seek consistency in how the Member States’ nationality laws align with the EU’s collective governance and internal security concerns, without infringing on their sovereignty.

The European Union’s scrutiny of CBI programs also largely stems from concerns about potential financial illegalities, such as money laundering, tax evasion, and corruption, which might be facilitated through these schemes. While the EU Commission and Parliament have highlighted the necessity for Member States to implement stringent safeguards to mitigate these risks, aligning with the principle of sincere cooperation, it is essential to contextualize these concerns within the broader landscape of global financial flows.

Financial crimes are increasingly a feature of our interconnected global economy, where capital moves freely and rapidly across borders. This environment, rather than the CBI programs themselves, provides fertile ground for illicit financial activities. It is a nuanced issue where the potential misuse of CBI schemes by a minority of applicants should not overshadow the legitimate use by the majority. The direct linkage between CBI schemes and financial crimes often relies on exceptional cases rather than a systematic analysis or empirical evidence demonstrating a pervasive trend among CBI applicants towards financial misconduct40.

To address these concerns effectively, a more balanced approach is required. Enhancing the due diligence processes and transparency in CBI schemes, as well as strengthening monitoring mechanisms, can significantly mitigate the risk of these programs being exploited for illicit purposes. Compliance with Anti-Money Laundering (AML) standards is crucial in this regard. By adhering to robust AML protocols, Member States can minimize the risks associated with financial crimes without necessarily penalizing states offering CBI programs or the individuals legitimately seeking citizenship through investment.

In sum, while it is vital to be vigilant about the risks of financial crimes in the context of CBI schemes, it is equally important to recognize that these risks are part of a larger global challenge. Effective due diligence and adherence to AML standards can serve as potent tools in ensuring that CBI programs remain legitimate avenues for citizenship without becoming conduits for financial irregularities.

In this context, following the Parliament and the Commission’s recommendations and the commencement of the infringement procedure, Malta adopted a new scheme on CBI, aiming at enhancing its transparency and due diligence, demonstrating a prompt willingness and initiative to engage in sincere cooperation with the European Union and its Member States. This effort by Malta to provide greater transparency in the Citizenship by Investment (CBI) processes results in the fact that individuals who receive citizenship are less inclined to commit financial illegalities, given that they are investigated and monitored even after the acquisition of citizenship.

Malta’s response to the accusations

After the Commission filed its claim, Malta implemented fresh regulations concerning the Citizenship by Naturalisation for Exceptional Services by Direct Investment Scheme (CESDI), modifying the preceding program. These alterations have targeted at addressing concerns voiced by international stakeholders, bolstering program integrity, and guaranteeing adherence to EU law and norms. The revisions to CESDI encompassed modifications to eligibility criteria, investment prerequisites, due diligence protocols, and transparency standards. Amendments were enacted to synchronize Malta’s citizenship by investment initiatives with advancing international standards and optimal practices in the realm of citizenship and residency by investment41.

The Community Malta Agency42 has implemented a comprehensive four-tier due diligence process to ensure that each application undergoes thorough examination consistently and that decisions are made in a systematic and transparent manner. This procedure directly responds to the concerns raised by the Commission and the Parliament regarding money laundering and terrorist financing. The Agency’s risk matrix covers various aspects, including identification and verification, business and corporate connections, politically exposed persons, sources of funds and wealth, reputation, legal and regulatory considerations, and the potential impact on the main applicant’s immediate network. Such is the case that Malta’s program has been ranked first overall in the Transparency Index of CBI schemes by the Investment Migration Insider since 202243.

Exploring the ECJ judgment's broader implications on CBI schemes around Europe

The ECJ’s decision will likely hinge on whether Malta’s CBI´s is found to be compatible with the principles and objectives of EU law, particularly in terms of its impact on the rights associated with EU citizenship, the principle of sincere cooperation and the genuine connection concept, and the protection of fundamental rights. The court will balance Malta’s sovereignty in nationality matters against the scheme’s potential to affect EU interests and values negatively.

The ECJ has consistently recognized that the determination of the conditions for the acquisition and loss of nationality falls within the competence of each Member State. This principle is grounded in the fact that EU treaties do not provide the EU with direct competence over nationality matters, which are considered at the core of national sovereignty. In this regard, it is plausible that the ECJ will render a decision affirming the legality of Malta’s CESDI scheme, thereby determining that matters pertaining to the criteria for the renunciation and conferment of nationality remain within the purview of the sovereign prerogatives of Member States.

Should the ECJ decides that Malta’s Citizenship by Investment (CBI) scheme is compatible with EU laws and treaties, the decision could have several broad impacts:

-

- Such a decision would effectively validate the legality of CBI schemes within the EU framework, potentially encouraging other Member States to maintain existing schemes or consider implementing new ones.

- The decision might lead to the development of a more defined framework or set of guidelines for CBI schemes across the EU.

- A ruling in favor of Malta’s CBI scheme could attract more investors to similar programs in the EU, boosting investment inflows. This could be particularly appealing for smaller or economically weaker Member States looking for ways to stimulate economic growth and attract foreign capital.

- The decision could reinforce the notion that EU citizenship, with its attendant rights and freedoms, can be granted under conditions set by individual Member States, including through investment or any other form permitted by law.

- The ECJ might highlight the need for harmonization or coordination among Member States to ensure that such schemes do not undermine the integrity of the EU or its internal security. This could lead to efforts to align these programs more closely with EU policies and standards.

On the other hand, in the unlikely situation of the ECJ rules against Malta’s CESDI scheme, the implications could be far-reaching and multifaceted:

-

- Precedent for CBI Schemes: Such judgment would set a precedent that could restrict or even end the practice of CBI within the European Union, asserting that such schemes are incompatible with EU laws and treaties.

- Impact on Existing Programs: Member States with existing CBI schemes might be compelled to revoke or substantially modify their programs to align with EU norms and principles, particularly regarding the acquisition of citizenship.

- Investor Uncertainty: The decision could create a climate of uncertainty for potential investors and those who have already obtained citizenship through investment. It could also deter the use of investment as a basis for acquiring citizenship, affecting the appeal and operation of such schemes.

- Strengthening EU Sovereignty: A ruling against Malta could be interpreted as a move to strengthen the EU’s federalism over nationality sovereignty, emphasizing the importance of a genuine connection between the individual and the Member State.

- Amplification of EU Competence: The decision would amplify the extent of the EU’s competence in regulating national citizenship policies, potentially leading to a deeper integration of national policies within the EU legal order.

Looking toward a critical juncture for national sovereignty and EU law

The ECJ’s forthcoming decision on Malta’s CESDI scheme represents a critical juncture in the intersection of national sovereignty and EU law. At the center is whether Malta’s CBI scheme aligns with the principles and objectives of EU law, particularly concerning EU citizenship rights, the principle of sincere cooperation, the genuine connection requirement, and the safeguarding of fundamental rights. The ECJ’s deliberation will necessitate a careful balancing act between respecting Malta’s autonomy in determining nationality criteria and addressing the potential implications of the scheme on broader EU interests and values.

Given the ECJ’s historical stance that the determination of nationality conditions falls within the purview of individual Member States — a principle underscored by the absence of direct EU competence over nationality matters in EU treaties — it is conceivable that the Court will uphold the legality of Malta’s CBI scheme. Such a decision would not only affirm the sovereignty of Member States in nationality matters but could also set a precedent for the legality of CBI schemes within the EU.

A ruling in favor of Malta’s scheme could have several significant consequences. It might catalyze the maintenance or introduction of similar schemes by other Member States, prompt the development of a more standardized EU framework or guidelines for CBI schemes, and enhance investment inflows into the EU, particularly benefiting smaller or economically weaker Member States seeking economic growth and foreign capital. Furthermore, it could underscore the principle that EU citizenship, along with its associated rights and freedoms, may be granted under conditions determined by individual Member States, including through investment.

An adverse ruling from the ECJ on Malta’s CBI scheme could not only establish a restrictive precedent against investment-based citizenship in the EU, but also heighten investor uncertainty, as it underscores the EU’s escalating dominance over national citizenship regulations. Such a decision might signal a decisive shift towards EU federalism, challenging the autonomy of Member States and potentially steering the Union towards a more centralized approach to nationality laws. It would also mark a departure from both ECJ’s precedent and dominant international law that traditionally upholds state sovereignty in matters of nationality, challenging the established autonomy of Member States and potentially reshaping the EU’s approach to citizenship policy. This decision could catalyze a new era of EU federalism, signaling a significant shift in the balance of power between national sovereignty and EU jurisdiction over citizenship laws.

References

1 Investment in citizenship and residency programs enables foreign investors to establish themselves and enjoy free movement in certain global regions. Citizenship by Investment (CBI) schemes confer nationality and all associated rights, whereas Residence by Investment (RBI) schemes provide a residence permit, which may eventually lead to citizenship. This report will primarily focus on the Maltese CBI scheme, highlighting the European Commission’s decision to refer Malta to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) due to the implementation of this scheme.

2 Surak, K. (2023) The Golden Passport: Global Mobility for Millionaires. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

3 Malta. Legal Notice 450 of 2013 – Individual Investor Programme of the Republic of Malta Regulations, 2013, Government Gazette of Malta No. 19,187 – 24.12.2013. Available at: https://legislation.mt/eli/ln/2013/450/eng/pdf

4 Launched in 2014, the Maltese Individual Investor Programme (IIP) was succeeded by the Citizenship by Naturalisation for Exceptional Services by Direct Investment Scheme in 2020. Over its six-year duration, it awarded citizenship to 1,800 applicants, with Prime Minister Robert Abela noting a 60% success rate for applications. The program generated more than €1.5 billion in revenue during this period. Martin, I. Cash for passports: EU threatens legal action against Malta. Times of Malta, June 16, 2021. Available at: https://timesofmalta.com/article/cash-for-passports-eu-threatens-legal-action-against-malta.877976. By the end of 2023 the MEIN was forecasted to generate another €900 million. Martin, I. Passport profits forecast to drop by €40 million next year. Times of Malta, October 20, 2022. Available at: https://timesofmalta.com/article/passport-profits-forecast-drop-40-million-next-year.990125

5 Cyprus has phased out its CBI program and is not accepting any application since 1 November 2020. Alternative routes for relocation in the country is Cyprus Golden Visa. See more at: Global Citizen Solutions. Cyprus citizenship by investment suspended. Available at https://www.globalcitizensolutions.com/cyprus-ends-citizenship-investment-program/.

6 European Commission (2020). Investor citizenship schemes: European Commission opens infringements against Cyprus and Malta for “selling” EU citizenship. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1925

7 Malta. Legal Notice 437 of 2020 – Subsidiary Legislation 188.06 of 2020. Granting of citizenship for Exceptional Services Regulations. Available at: https://legislation.mt/eli/sl/188.6/eng/pdf.

8 Malta. Legal Notice 435 of 2020 – Subsidiary Legislation 188.05 of 2020. Agents (Licences) Regulations Available at: https://legislation.mt/eli/sl/188.5/eng/pdf.

9 European Parliament, ‘Resolution of 16 January 2014 on EU citizenship for sale’ (2013/2995(RSP)) (European Parliament Resolution 2013/2995); European Parliament’s Resolution on CBI and RBI programmes (2021/2026(INL)), European Parliament, ‘Resolution of 1 March 2022 on the Russian aggression against Ukraine’ (2022/2564(RSP)) (European Parliament, Resolution 2022/2564(RSP)).

10 European Commission, (2022). Investor citizenship scheme: Commission refers MALTA to the Court of Justice, Press Release, 29 September 2022, Brussels. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_5422

11 European Parliament (2014). Plenary Session debate. Speech: Citizenship must not be up for sale, Brussels, 15 January 2014. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_14_18.

12 European Parliament (2014). European Parliament resolution on EU citizenship for sale, Brussels, January 2014. (2013/2995(RSP)). Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/B-7-2014-0029_EN.html.

13 European Commission (2014). Joint Press Statement by the European Commission and the Maltese Authorities on Malta’s Individual Investor Programme (IIP), Brussels, 29 January 2014. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_14_70.

14 European Parliament (2017). European Parliament resolution of 15 November 2017 on the rule of law in Malta (2017/2935(RSP)). Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2017-0438_EN.html.

15 European Parliament (2019). Resolution of 26 March 2019 on financial crimes, tax evasion and tax avoidance (2018/2121(INI)). Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019IP0240.

16 European Parliament (20129). A comprehensive Union policy on preventing money laundering and terrorist financing – the Commission’s Action plan and other recent developments, Brussels, 10 July 2020. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0204_EN.html.

17 European Commission (2020). State of the Union Address by President von der Leyen at the European Parliament Plenary, Speech, 16 September 2020, Brussels. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_20_1655.

18 European Commission (2020). ‘Golden passport’ schemes: Commission proceeds with infringement case against MALTA. Press Relase, Brussels, 6 April 2022. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_2068 .

19 See notes 7 and 8.

20 European Commission (2022). Commission recommendation on immediate steps in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in relation to investor citizenship schemes and investor residence schemes of 28 March 2022, Brussels, para 3.

21 European Commission (2022). Investor citizenship scheme: Commission refers MALTA to the Court of Justice. Press Release, 29 September 2022, Brussels.

22 Community Malta Agency (2022). The Government of Malta takes note of the action taken by the European Commission. Press Release by the Ministry for Home Affairs, Security, Reforms and Equality, 29 September 2022. Available at: https://komunita.gov.mt/en/2022/09/29/the-government-of-malta-takes-note-of-the-action-taken-by-the-european-commission/.

23 European Commission (2019). Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Socila Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Investor Citizenship and Residence Schemes in the European Union, Brussels, 23.1.2019, COM(2019) 12, p. 1.

24 Kochenov, D., Basheska, E. (2022) It’s All about Blood, Baby! The European Commission’s Ongoing Attack against Investment Migration in the Context of EU Law and International Law, Working Paper No. 161, November 2022.

25 The passing of citizenship through descent (blood) represents an inherent mode of nationality transmission. Unlike the process of naturalization, which implicates individual volition, citizenship by descent embodies a tacit process akin to a “birth lottery”. Consequently, one might expect a stronger foundation for genuine ties between descendants and the nation granting citizenship. However, in practice, the sole requisites typically include proof of consanguinity and a negative naturalization certificate of the ancestor in another country.

26 Tintori, G. More than one million individuals got Italian citizenship abroad in twelve years (1998-2010), Global Citizenship Observatory, European University Institute. Available at: https://globalcit.eu/more-than-one-million-individuals-got-italian-citizenship-abroad-in-the-twelve-years-1998-2010/

27 Law n. 132 of 01/12/2018 establishes that the recognition of Italian citizenship under the terms of articles 5 and 9 of Law n. 91 of 05/02/1992 can only be granted with proven and adequate knowledge of the Italian language.

28 Kochenov, D., Basheska, E. (2022) It’s All about Blood, Baby! The European Commission’s Ongoing Attack against Investment Migration in the Context of EU Law and International Law. Working Paper No. 161 November 2022, p. 9.

29 Ibid., p. 11.

30 The data used to produce the charts 1 and 2 were retrieved from the GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset – Modes of Acquisition of Citizenship. Available at: https://globalcit.eu/modes-acquisition-citizenship/

31 The data used to produce the charts 3 were retrieved from the IMI Data Center. EU Citizenship by Ancestry/Descent Policies. Available at: https://www.imidaily.com/eu-citizenship-by-descent/

32 See Article 1 of the Convention on Certain Questions Related to the Conflict of Nationality law, 13 April 1930, The Hague. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/legal/agreements/lon/1930/en/17955

33 See Article 3(1) of the 1967 European Convention on Nationality. Available at: https://rm.coe.int/168007f2c8.

34 Case C-200/02 (2004), European Court of Justice, [2004] ECLI:EU:C:2004:639, Case C-135/08 (2010), European Court of Justice, [2010] ECLI:EU:C:2010:104 and Case C-221/17 (2019), European Court of Justice, [2019] ECLI:EU:C:2019:189.

35 Article 20 TFEU, ‘every person holding the nationality of a Member State shall be a citizen of the Union’.

36 Article 4(1) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU).

37 Micheletti: “Under international law, it is for each Member State, having due regard to Com- munity law, to lay down the conditions for the acquisition and loss of nationality.”

38 Dimitry Kochenov, Daniel Sarmiento, Hans Ulrich Jessurun d’Oliveira, Martijn van den Brink among others.

39 On March 28, following the Russian invasion in Ukraine, the Commission recommended that any Member State which has granted citizenship to Russian or Belarusian nationals through an investor citizenship scheme should promptly undertake a review. This review, in alignment with the jurisprudence of the ECJ, should adhere to the principles of proportionality and the safeguarding of fundamental rights. The purpose of this assessment was to determine whether the naturalization of these individuals ought to be revoked. European Commission (2022). Commission recommendation on immediate steps in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in relation to investor citizenship schemes and investor residence schemes of 28 March 2022, Brussels.

40 Community Malta Agency. Acquisition of citizenship by Exceptional Services and Direct Investment. Available at: https://komunita.gov.mt/en/services/acquisition-of-citizenship/#ForExceptionalServices.

41 The IMI Citizenship Transparent Index 2024. Available at: https://www.imidaily.com/2024-cbi-transparency-index/.